Eccentric Subjectivity And Authenticity Fiction

From Becoming Disfarmer, Edited by Chelsea Spengemann

Published by The Neuberger Museum of Art, 2012

I.

Photographic portraiture has become so universal within contemporary experience, so unremarkable and transparent, that we perceive its disruption of the history of portraiture only vaguely. By the late nineteenth century, photography seemed to offer a refiguring of the classical paradigm of portraiture once typified by court painting, more apt to industrialized modernity and its increasingly flattened social structures. Its easy and inexpensive reproduction implied an equitable reinvention of the genre, accessible to and practicable by nearly anyone, regardless of class. [1] Prior to this era, formal portraiture was the right and writ only of those with the means to commission it, the fact of which necessarily inscribed the portrait image with the subjects’ chosen narratives of themselves.

The pictorial reflection of that liberation was to be photography’s alleged essentialism, its potential as a quasi-automated mechanism to depict neutrally and absolutely, in contrast to the manually crafted rendering of traditional plastic arts such as painting, drawing, and sculpture. Synchronous with the widening of economic and social opportunity, the advent of machine vision would provide the public a parallel form of access that was epistemological rather than strictly material. Photographic portraiture was presumed to be a conduit to our authentic selves, at once universal and concretely individual: the newly identified and named photon that reflected from the face of a portrait subject registered not only an indexically accurate trace on the atoms of an engineered film emulsion, but an equivalent quantum of human knowledge. As a direct example of shared social experience, the idiom would thus be a spontaneous generator of real meaning. The medium’s technologically perfected surface would provide an amalgamation of raw facticity that inverted the classical portrait paradigms of an exclusive and idealized subjectivity, the foil to which could be found in the persistence of the underlying humanist portrait motive: the great reveal of our commonality.

Yet none of this actually happened. Instead, what well-intentioned humanist photographers throughout the twentieth century ended up illustrating indirectly was that the pure ideal of a new civic portraiture as categorical imperative was effectively impossible, that the images thus produced could for all their moralism be instrumentalized nonetheless, if to other, newer ends, including and especially those assumed to be beneficent. Ethnographic photography, for example, invoked as objective proof by the burgeoning field of anthropology, could also resemble the colonial impetus, if manifest only visually. What had in the early stages of photography appeared as a liberating potential to depict the modern reorganization of older social orders ultimately showed itself to be a continuation of the traditional agenda of projection, practiced by different means and, more importantly, upon different subjects, willing or otherwise.

While the tendency of portraiture to mythologize remained constant, to the older tradition of edifying established power was thus added the modern variant of monumentalizing the everyday and the outlying. The omnibus photographic portrait projects of August Sander and Edward Curtis exemplified two such modalities. Sander’s attempt—hopeful when understood contemporaneously, foreboding in retrospect—was to limn a unified totality of the public sphere, Curtis’s to eulogize another social history already in the process of being effaced by the one in which he himself was a participant. Both projects were ultimately inventions of their makers. Grandiose and beloved because they arrive to us now not at all as the data of knowable experience but as prompts for the subconscious reclamation of a tantalizing past, they are unknowable all the more for the revelations they allege. Unable ever to adequately account for the contradictions in its projected images, humanism’s self-deception comes full circle in the narcissistic fascination with its own repression. How else to account for the perpetuated circulation of projects like Curtis’s, when we’ve not only learned that so many of his images were actually setups, but when we also come to understand that, as portraits, they are all fundamentally misdirections?

Despite the avowed interest in the specificity of content as the source of meaning (see the tattered vest of Sander’s bricklayer), it is rather the generalized form of photographic portraits as neatly reflective screens for those ideological projections that enables their usefulness. No doubt there are as many different possible dynamics of the portraiture genre as there are between people, but all of them reach their contestatory apex as competing myths in the contrast between private and public portraiture.

We might distinguish the private portrait from all others as one depicting a person with whom a viewer shares a direct relationship beyond the image shown. Private portraiture thus implies a meaning intrinsic to the creation, ownership, or viewing of a portrait that is not transitive: I keep this portrait as a precipitation of the interpersonal experience between us. That meaning cannot be integrally sustained beyond the direct relationship between the private parties of the viewer and the viewed. Even if the portrait changes hands to another (perhaps loved) one—a portrait of you first taken for your daughter has since been handed down to hers—its meaning shifts in parallel with the different relationships. Private portraiture has a fixed meaning, separate even from the photographic object that is its sedimentation, derived from a specific one-to-one relationship between people. It is a conundrum, vivid even as it replaces the subject it represents; and it is also a model, consummate among all photography genres, of lived experience, one hinged along the axis of that conundrum of knowability, so recognizable in its form and charge yet, like its subject, perpetually just beyond the horizon of complete apprehension. Not at all a case for alienation, private portraiture is in its plenitude, its abundance of promise, nonetheless exemplary of that state of cognitive exile that we rightly recognize lived experience to be. It is therefore the private portrait’s double aspect, bittersweet but neither negative nor even undesirable, that invokes both the loved one as well as an awareness, not simply of his or her possible absence (Barthes’ that-has-been), but of our own avowal to find meaning within that continual state of incompletion. It is finally this action—to create private portraits in the knowing acknowledgment of both the union and absence they portend—that makes photography a meaningful model of living, unique in this way among other acts of picture making.

Public portraiture, having been either deliberately or subsequently shorn from that meaning of relationships, is commonly exploited to displace precisely those same intrinsic personal bonds: it is a spectral void-fill, hoisted up (up because it is intended for mass viewing, up above the crowd and the individual for a clean line of sight beyond the reach of both, up for spectacular scale, up, invariably, to incite) and used as a screen upon which we can project any manner of desired ideas to substitute for that now-missing private meaning. Though linked in a dependent relationship to the desire for closeness implicit in private portraiture, the purpose of public portraiture is to exploit that desire in order to supplant its subject completely. It differs from the private experience of portraiture because it is engineered to eliminate the conundrum of emotional dissonance and any consequent complexity: public portraiture is operationally efficient, a means to some intermediate purveyor’s ends, and most often purified of the emotional contradictions involved in viewing a past image of someone known personally. As a communication, it is by nature wholly transitive, deliberately intended for the largest number of audiences possible, and thus the diametric opposite of the private portrait. It is the universal instantiation of persona (a generic category, rather than the individuated identity of a human subject) as ideology and value. It becomes, in its final form and effect, a currency. It is a lever for substituting value, empty of intrinsic meaning and empowered by the velocity of its transferal.

Note, most critically, that public portraiture, while commonly practiced as the wholesale creation of an image (as in the genres of political and celebrity portraiture), can just as easily appropriate material previously made as private portraits. Its displacement of the interpersonal bond thereby becomes all the more powerful, presuming as it does the unmistakable air of authenticity that no staged form of public portraiture can attain. It is exactly that co-optation of direct experience that all public portraiture seeks for its power, and thus for its valuation as currency.

II.

How then to read Disfarmer, or what to make of what has already been made of it? It, and not him: the phenomenon of “Disfarmer,” to be understood apart from either the person originally known as Mike Meyer or the photographs he made. Meyer’s earlier concoction of the Disfarmer persona has dovetailed with the later embroidery of his photographs’ significance, and of their signifying, as the obscure contours of his own biography enable a similarly fascinated haymaking off his subjects. Nearly as much time has now passed from the first major Disfarmer exhibition, organized by Julia Scully and Peter Miller in 1977, as between the exhibition and the creation of Meyer’s studio portraits in Heber Springs, Arkansas. Interest and interests in Disfarmer have accelerated since the late 1970s, so an adequate historicization of that name, of how it has come to mean and not, is clearly due.

Start then with the pictures themselves, which can largely be broken down into two stylistic periods. The earlier grouping, made as part of the business partnership of Penrose & Meyer, leans on misinherited totems of the Victorian era. Thus the Arkansas farmer in dungaree overalls, impossibly posed in front of a painted Acadian temple scene, complete with trompe l’oeil curtain swag and orientalist rug, several decades behind the fashion for that sort of Pictorialist mannerism (see Fig. 2). These are props as signals, meant to communicate some station of the subject, and as with any miscommunication they can unintentionally verge on slapstick. Similar devices persist in public portraiture now, if differently styled (see President Bush’s flight suit), as they have since ancient Rome. Photography was supposed to be different, of course. But Pictorialism missed its cue, as did the firm of Penrose & Meyer, which might be expected of a regional small business rightly in service to its customers and not to art history. These are private portraits only a mother should love.

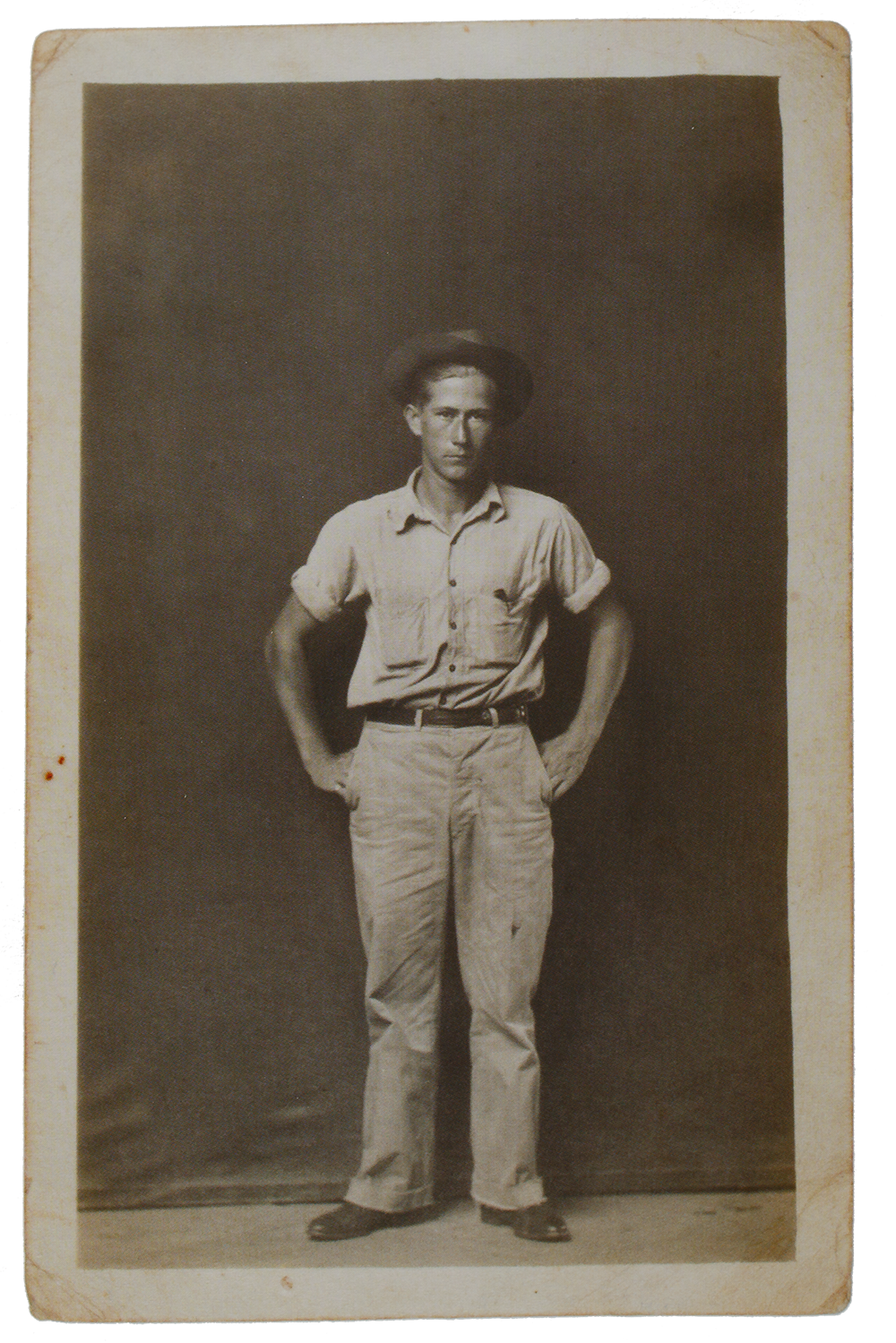

For his part, Meyer moved beyond Pictorialist tableaux at nearly the same time he moved beyond Penrose. Once established under his own shingle in Heber Springs, he came into the secondary style that has since come to be identified as Disfarmer. The contrast is informative. The later photographs shed kitschy allusions to the European salon tradition, and they are the more interesting for it. The scenically painted backdrop is replaced by the available make-do of plain studio flats, and a table is only used as an impromptu posing perch for smaller children, no longer as a prop. The focus is almost entirely on the subjects themselves, their expressions or lack of them, their coordinated Sunday dress, the tasty vintage details of hair or hat or tie or boot, on all the indicators, conspicuous or unself-conscious, of physical presence. This is unmistakably the stripped-down, serialized production of a frugally minded commercial photo studio on a small-town Main Street. It would be a stretch to call it modernism, but it is undeniably a reflection of modern times in one particular place, and that in itself had always been the promise of photography.

When a cross-section of one area’s population is depicted in terms so detached, it leaves us with artifacts of such plainness that they spur the desire for storytelling. That’s only natural. The peculiarly slack portrayal of subjects in Disfarmer portraits, as opposed to their traditionally overt confection, provides an especially tempting blank to write upon. There is nowhere to hide in the images—not for his subjects, who seem caught unawares surprisingly often, despite having presumably commissioned the portrait transactions, nor for us as viewers, left to reckon with the few other details in the pictures. (Note, for example, how much has been made over the significance of black stripes on the wall, whereby an incidental studio feature of a working commercial photographer, strapped for resources much less an architect, becomes grounds for debate: but what does it mean?) [2] While Meyer rarely varied from placing his subjects dead center in the frame throughout his career, the isolating effect was amplified when he switched to plain backgrounds, often leaving more negative space around his figures than strictly necessary given the absence of props and other visual elements (See Fig. 3 & 4). All of that emptiness above their heads seems to be wanting the reappearance of earlier painted boughs, as though Meyer had trained himself on a single compositional habit he picked up as a journeyman but never thought to revisit when his tools and times had changed.

No matter: one man’s oversight is another’s revealing idiosyncrasy, or genius. That carelessness is reframed as a vouchsafe for the genuine, proof that we’ve found something real. However, the liability of that conflicted mystification—of the desperate and common need to re-imagine what makes for reality—is that people who had been previously knowable in a private context have become public icons of a folksy host, transubstantiated from the flesh and imbued with ideological connotation for an audience understandably desirous of identification and connection.

To believe then in the coded ineffability of Disfarmer portraits as public monuments is likewise to avow rugged individualism as the ur-text of American identity. This is the opposite contention of August Sander’s lifelong work, which was the purposeful depiction of a society constituted as the collective of its citizens. Portraiture in America is prefigured as evidence of the sovereign subjectivity of the depicted, clean and somehow weightless of history, and if destined, then only for the freedom of pure selfhood, no matter whether noble or abject. Even Robert Frank’s appositely titled The Americans functioned not as a refutation of this convention, but as an indictment of its politics alone, one that nonetheless affirmed its standard visual form. His urban cowboy and black bus rider alike still appealed to an ideal of lone sovereignty, as he had not yet pushed his portraiture to the point that it might shift its core pictorial function away from essentialism.

Meyer’s unadorned scenes, his straight-on angles, the period of economic struggle between world wars, the Deep South setting, and the frequently gothic expressions of his sitters all seem of a piece with the easy presumption that he was capable of showing some truth about the hardscrabble decency of certain American classes. The message preferred by his interpreters ever since has been that, by 1939, Meyer qua Disfarmer had entered the realm of American forthrightness and photography’s essential honesty: to look at these portraits is to touch the true face of human heritage, and so on.

None of which is to say that some of the pictures aren’t indeed compelling or to discredit Meyer’s knack as a photographer, which could occasionally be fortuitous. It is simply to say that none of that is material to the discussion at hand, which involves issues wholly separate from either those criteria or any of the other personal meanings originally behind the creation and ownership of the portraits. What has come to us by now under the rubric of Disfarmer are the effects of different motivations, obscured as they must be under misleading discussions of authentic lives, rather than clarified by the direct awareness of what previously private portraits amount to when made public. There isn’t nothing to see here; those concrete historical specificities of the pictures are undeniably potent on the aesthetic and gut-emotional level, as good mystery fiction will be. But neither can there be for us any intrinsically knowable meaning to them beyond their use-value as public portraits, or, alternatively, as grounds on which to base a more nuanced critique of such instruments.

The Disfarmer phenomenon then has become a compounding of identity manufacture: of Meyer’s own and those of his portraits, of what we allege of his subjectivity and of his subjects. [3] That symmetry may or may not have derived from Meyer’s own doing; it may not have ever been his own strategic intention, nor anything he even dreamed of. Be that as it may, Disfarmer by now has effectively become Meyer’s self-portrait, the melding of the Disfarmer persona with the Disfarmer photographs as twinned acts of wishful creation. Myth begets myth.

It is impossible at this late point to genuinely understand—to know—the reasoning behind Mike Meyer’s adoption of the Disfarmer persona. The most frequent tendency has been toward a grandiloquent caricature of the reclusive and unrecognized visionary. Meyer’s own few surviving statements are mostly fantastical disavowals, rather than anything like a substantial statement of self or working method, and as tall-tale fragments from a grown man go, they play directly into the established theme of Meyer as town crank. Interpreters since haven’t gone far to unpack that. The assumption of his eccentricity, progressively varnished as much by the scarcity of biographical details as by the surplus of other, more colorful bits (spanning from the hurricane creation legend authored by Meyer himself to gossip about the loner, found days after his solitary death in a squalid studio), well suits the notional pre-requisite of the modern artistic sensibility. More than a lyrically allusive name, the mononym has come to be invoked as the badge of a certain mystique, and as such, it offers the plenitude of the cipher: its impenetrability is understood to be to its advantage as an intriguing artifact, rather than to its detriment as a source of knowledge and meaning.

All of the unelaborated ambiguities in the dual tracks of Meyer’s life—in his creation of Disfarmer or his creation of the portraits—could therefore be positioned as denoting whatever one seeks in them: eccentricity, for example, becomes the rarified indicia of authenticity in a society of industrially induced standardization, and authenticity in turn certifies value. This is the operation of public portraiture. Similarly, any presumptive portrait meaning, assigned either to the picture of “Disfarmer” or to Disfarmer’s pictures, must therefore be understood to be one and the same operation, an attempt at recuperation that is exclusively concerned with the demands of third parties, and nothing that in any way can be attributed to either Meyer the photographer or the original subjects depicted in his photographs. [4]

Has it been noted, for example, that most of the later Heber Springs studio negatives were assembled for their first publication by two people alone, and a vast number of remaining “vintage” prints—itself a largely market-driven concept of legitimation—by one other individual? That the former were responsible for first bringing wide public notoriety to the Disfarmer name, and the latter has led an openly self-described “reclamation project,” paying families still in possession of Disfarmer portraits of their relatives to part with them for their public exhibition as part of his assembled archive? That two of these people have created competing cottage businesses around the merchandising of their respective collections, effectively cornering the Disfarmer commodities market? (Of one’s similar purchase of the entire estate of Dmitri Baltermants, a reporter has written: “Collector Michael Mattis aims to make an obscure dead Russian photographer famous. If he can, he’ll make himself richer.”) [5] Have any of these factors been substantially discussed in the context of how we have come to recondition these previously private portraits as art objects and presumptive truths?

We risk missing just as much, however, by ascribing the totality of the Disfarmer phenomenon to market considerations alone, which do not adequately account for the basic appeal of the pictures. In fact, it is their instinctual pull on us as portraits that has driven their steady circulation. That pull demonstrates much wider interest in Disfarmer than the monetary, one that verges on the spiritual in its fixation on assumed truths. Various writers on Disfarmer have said that “these photographs portray with truth and power,” [6] that they make for “an encounter with art of the rarest kind…of touching intimacy and epic heroism.” [7] They “reveal with immense, uncanny power the pride, stoicism, simplicity and clannishness of the plain country people,” they “reveal an essential human quality,” the “sitters reveal themselves with an innocence and trust.” [8] Language like this was a prosaic part of photographic criticism prior to post-modernism, but it begins to indicate something specific when spoken in relation to Disfarmer, something that points to a broader cultic fiction about authenticity.

Authenticity fiction is one more pop literary genre, though more typical of a late media age than noir or sci-fi: it is the recitation of an abject visual repertoire deludedly cited as proof of real experience, the unironic synthesis of favored documentary tropes long past the point of their viability. It seeks the exploits of previous and lost generations just as it does those of today’s most fashionable youth. It is stories of the open road, of anti-hero worship, of beautiful taboo, of impoverished self-made pioneers better and freer and more pure than we are. It consecrates itself to the romantic ideal of an eternal present, to the holy of the here and now, though in presentation it is always looking elsewhere. It is a fawning fascination with the Other that masks a parasitism, an inverted xenophobia that dehumanizes just the same by turning identity into image, breathlessly expressed rather than paranoically repressed. It is, ultimately, childish. Of course authenticity fiction finds its natural home in photographic portraiture, [9] where the intense contradictions of image, fact, and meaning can make it too painful to consciously acknowledge the inevitable gulf between the viewer and what one wants to believe is viewed. Desire outlives that collapse, so the portrait must be subconsciously reconfigured: from private memory to a broadly fungible motif, monetizable because it satisfies the yearning for a sense of personal identification and experience that never existed to begin with.

Robust photographic criticism challenges that fiction because it involves ongoing reconsideration of the personal, social, economic, historical, and ideological underpinnings of any such transaction. It requires the frank admission of an infinitely complex array of decisions and concessions between players, so that what we can surmise from the aftermarket phenomenon of Disfarmer need not have anything directly to do with the putative subjectivity of the photographer Mike Meyer. When so little is known about Disfarmer, to ascribe motivations to that subjectivity would be to compound and paper over the same instrumentalization that a critique of the thing called Disfarmer would attempt to flush out. We can never truthfully intend any form of recuperation of the authenticity of either the photographer, his portrait subjects, their motivations and meanings, or the bonds and qualities intrinsic to the original portraits, all of which inevitably remain unknowable to us. We can only seek to base that critique upon Disfarmer as a case study of how photographic portraits come to mean and not mean as collective experience.

III.

What final possibilities might there yet be, for us as outsiders, to find meaning within the Disfarmer images? Photographic portraiture is an idiom with implications of its own to reckon with, rather than the transparent document it has historically been assumed to be, and it is the confluence of these implications that ultimately yields the putative meanings of what we know as “Disfarmer,” be that a photographer, a mythology, a market, or a historical archive. As a lucid viewer, to look upon a nonprivate portrait—that is, a portrait of someone whom you have not known privately, but a portrait that you also consciously refuse as a public myth—is to experience it only as someone else’s shorthand, complete and recognizable in itself while unreadable as such, full of the promise we imagine in strangers, but devoid of any intrinsic meaning beyond its function for you as an experiential model of exile. That in itself is not without its humanity.

“Expressionless expression,” [10] Theodor Adorno’s negative inversion of aesthetic possibility, did not foreclose all avenues to creation, for all its merciless rigor as critique. It implied that an idiom, emptied of its attendant connotations as an illustration of something or someone else and thus ideologically freighted with metaphor and allusion, might become instead an autonomous model of thought and experience in and of itself. This begins with the resolution to resist the temptation so common in portraiture to disingenuously essentialize the subject, to knit the preferred fictions of authentic identities. Meaning does not come from the exactness with which photography depicts incident, but from its elision of the same, from its always oblique approaches toward that horizon in a series of ever nearer misses. That can get slippery. The clarity that photography provides—its sheer abundance of accurate data—is too readily mistaken for knowledge itself. That allure becomes unbearable when it is each other whom we are promised we might know.

But a portrait need not be presumed to possess some ineffable essence of the person depicted in order to be a meaningful exercise. The state of conscious exile it models—our asymptotic relationship to one another, perpetually separated by an infinitely thin margin—can mean more because that is indeed something we can experience directly, in real time and for ourselves, simply by looking. It’s that paradox that is the knowing in portraits, as close to real meaning as the form provides. We can never partake in the separate meanings of another’s private portrait, but we can feel its power and dynamic through our separation from it instead. So it is with all portrait surfaces. That in itself is enough.

Notes

For Felix Ensslin.

I am indebted to Nicolás Guagnini for his conversation and close reading during the writing of this essay.

[1] Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing in 1862 of the proliferation of cartes de visite: “Card portraits as everybody knows have become the social currency, the green-backs of civilization.” He could just as easily have referred to tintypes or any of the other cheaply produced portrait formats of the day. Oliver Wendell Holmes, “Doings of the Sunbeam,” Atlantic Monthly, July 1863, 12.

[2] Julia Scully, “Heber Springs Portraits,” in Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits, 1939–1946, by Julia Scully and Peter Miller (Danbury, NH: Addison House, 1976), 3: “His props were minimal: a couple of crude wooden tables and a bench; for background, a black roll-down curtain or a white wall inexplicably striped with black tape.” Numerous subsequent articles quote Scully almost verbatim.

[3] Other examples of posthumously refigured practices include those of E. J. Bellocq, Vivian Meier, and, most notably for all their assumed meanings as self-portraits, the photographs of Francesca Woodman.

[4] Examples of how the Disfarmer pictures have been co-opted by third parties for various ends include Bill Frisell’s 2009 album “Disfarmer,” Dan Hurlin’s 2009 puppet show “Disfarmer,” as well as the ongoing reference to the portraits as inspiration for fashion. Perhaps most indicative of their uprooting, however, was the 2007 lawsuit brought against poet Richard Howard for his fictionalization of Disfarmer subjects in a 2004 poem. The subjects sued Howard for “defamation, invasion of privacy, false light, and intentional infliction of emotional distress” as a response to the poet’s projected idea of their lives. See Arkansas Court of Appeals, Division 1, Feb. 25, 2009. The point to stress, however, is that even without going as far as these especially vivid cases, it is easy to see how the instrumentalization of public portraits in general, as with the Disfarmer portraits specifically, begins immediately with their circulation, as a structural fact of their very constitution. Further manipulations by yet other parties are, in this sense, merely obvious repetitions of the original displacement occurring within the portrait image itself.

[5] Susan Adams, “Red Eye,” accessed Feb. 2014, Forbes.com, June 7, 2004.

[6] Tara Collins, “Three Reviews,” NY Arts Journal, Spring 1977, 40.

[7] Owen Edwards, “Exhibitions: The Way We Were,” American Photographer 9, no. 2 (Aug. 1982): 20–22.

[8] Country Journal, review, Dec. 1976, as cited on Disfarmer.com, accessed Feb. 24, 2014; Louis Sahagun, “Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits,” review, Los Angeles Times, Feb. 6, 1977; and Charles Hagen, Art In Review, New York Times, June 9, 1995.

[9] As a pop genre, practitioners of authenticity fiction are innumerable, but among its exemplars have been Larry Clark, Ryan McGinley, Justine Kurland, Will McBride, and the tellingly pseudonymous Mike “The Polaroid Kidd” Brodie.

[10] Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998).

© Copyright Gil Blank

Eccentric Subjectivity And Authenticity Fiction

Eccentric Subjectivity And Authenticity Fiction